Jamaican photographer and actress Esther Anderson—a former girlfriend of Bob Marley and co-founder of Island Records—will showcase a collection of rare photos capturing the Reggae legend’s early years at an exhibition in London later this month.

Titled ‘Through the Lens of Esther Anderson: Bob Marley: The Early Years,’ the exhibition will feature 20 intimate photographs taken before Marley’s rise to international fame in the early 1970s. It will be held at the Muswell Hill Gallery, Hornsey, London N8, from May 30 to June 19.

Their connection began in 1972 when Anderson, co-founder of Island Records, first encountered The Wailers at Compass Studios in Nassau, Bahamas. This sparked a six-year musical and artistic collaboration with Anderson becoming a driving force behind the band, managing their early activities and documenting their journey in the studio, on tour, and even at their home base, 56 Hope Road. Her trusty Nikon Photomic FTN (1959) camera captured it all.

Anderson and Marley also had a two-year romantic relationship.

According to Stephen Davis’ 1988 biography “Bob Marley,” the Night Shift singer divided his nights between his wife Rita Marley and 56 Hope Road, where he was involved with Anderson.

“Rita Marley had birthed Bob’s second son, Stephen Marley, and left their Ghost Town house for a little house at Bull Bay in early 1972. Bob was alternatively living with her and sleeping at 56 Hope Road, where he was carrying on a torrid affair with Esther Anderson,” Davis wrote. He added: “Bob and Esther had started out as friends (she had been linked romantically with Marlon Brando and Blackwell), but a strong attraction soon drew them together and developed into something heavier. Bob also spent occasional nights with ‘the mothers of his babies,’ as the Jamaican euphemism goes.“

Davis had also noted that Bob and Ester were building a house in Negril by 1974. “[Her] allure was still intoxicating Bob. Half white and half Indian, the Jamaican actress was both beautiful and intelligent. She was also in some demand professionally; his most recent role had been in Warm December with Sidney Poitier. Bob was proud that she was his girl, and he and Esther were true friends.”

Anderson, now 80, emphasizes that her work does not “pander” to those who know Marley as a music icon. “My photographs reveal Marley beyond the bounds of a musician, as the messenger who could reach out to a global audience, a poet of past and future,” she says.

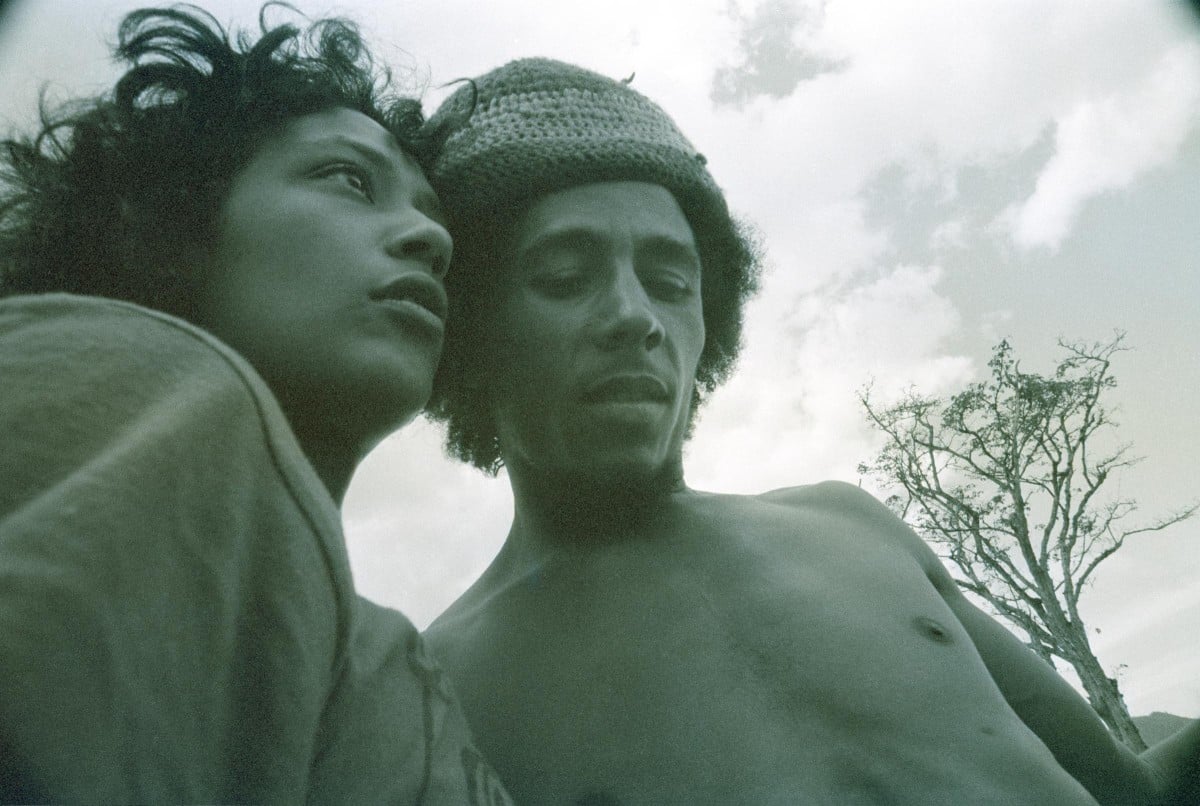

One striking image depicts a shirtless Marley on Hellfire Beach. “I wanted to photograph him in the light of Jamaica, showing the colour of our skin the way it should be shown,” Anderson explains.

Bob Marley at Hellshire Beach, Jamaica, in 1973. Photograph: © 1973 Esther Anderson

Bob Marley at Hellshire Beach, Jamaica, in 1973. Photograph: © 1973 Esther Anderson

Another of Anderson’s photos is the now-iconic image of Bob smoking ganja, which was used for the Catch A Fire album cover.

Photograph: © 1973 Esther Anderson

Photograph: © 1973 Esther Anderson

“That photograph was the first time anyone had been portrayed in that way, as he said he was ‘partaking of the sacred sacrament for his meditation’” she said. “The image became for Island Records a powerful marketing tool, but for the people an emblem of amnesty and freedom.”

“Long live the Power of the image, that’s what the photographs have for me.”

Anderson said she believed in The Wailers’ potential and championed their unique visual identity.

“Bob and the Wailers were hard-working, though they had been waiting for ten years in Jamaica without getting through, and the “Catch a Fire” album had not sold. To me, the Wailers had to visually represent what they said they stood for,” she said.

“I helped them to break free from the social constraints imposed on Rastafarian artists, to grow their locks, to take pride in who they were, and I did my best to communicate it to the world. When I took the picture of Bob smoking his herbs, and that image was spread around the world, the effect was a revolution. It broke all the moulds. The songs we wrote together translated what was happening in Jamaica at the time, the prejudice that the Rastafarian communities, suffered.”

7 months ago

77

7 months ago

77

English (US) ·

English (US) ·